Comics Are for Everyone: 1988 Edition [1988 Week]

/Because of the amazing comics that have been released in 1988, I decided to have another comics section in this theme week. Grant Morrison and Alan Moore are big enough names for this, I guess, but we shouldn’t forget Jamie Delano. I’ll just focus on the issues published in that year, since that’s enough already. Let’s go!

Grant Morrison restarted Animal Man in 1988 with Chas Truog (and those amazing Brian Bolland covers) and no matter what you think of Morrison now, but his run starts so irritatingly amazing that it is hard to imagine how people reacted to it back then. For one, he takes the idea of an Animal Man seriously, someone who actually learns to care about animals. In the first issue he fights a white superhero from Africa, after having seen some mutated monkeys in an American research institute.

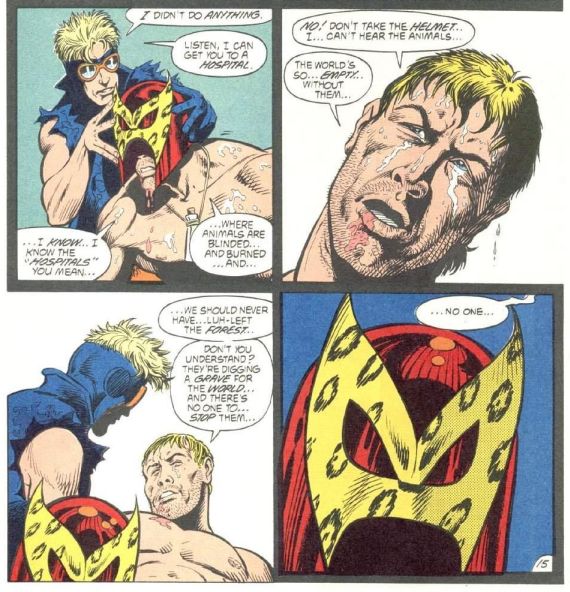

Animal Man #4 by Grant Morrison and Chas Truog

The defeated “White God” decries not only the treatment of animals for testing but only takes an environmental stance that maybe doesn’t sound strange, especially nowadays, but is still rare enough for comics, especially for its time. The idea that we’re ruining Earth is spelled out so starkly that it’s hard to ignore, though, as it is often the case, the one saying it here acts a bit radical. Writers always have a hard time giving challenging to people discussing them calmly and with reason, even someone as out there as Grant Morrison.

Animal Man #5 by Grant Morrison and Chas Truog

Animal Man reacts by going vegetarian. Sure, he acts radical (here we go again), but he still shows something we can do if we worry about our treatment of animals. His son’s reaction to tofu is very similar to how you see unknowing kids react still today.

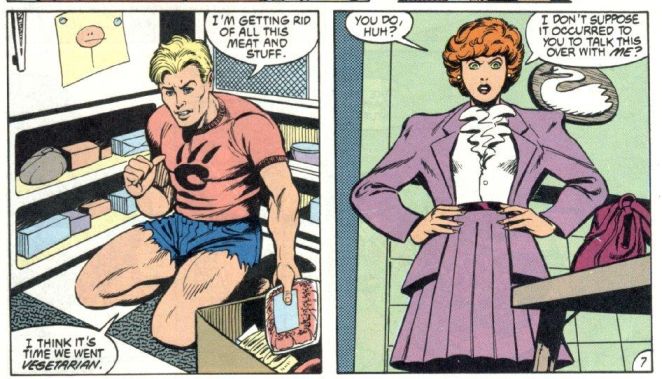

But let’s get to something else that Morrison did in Animal Man that, at the end of his run, made it really famous and that intrigues me more than anything else. He goes way into meta-fiction by challenging us to think of what it means to be creators of fiction. In one of my favorite comic book issues of all time, The Coyote Gospel, it all starts with looking at “cartoon violence” and Looney Tunes cartoons.

Animal Man #5 by Grant Morrison and Chas Truog

Showing them as world of “violence and cruelty”, is so brilliant because you instantly have to rethink how you’re seeing them. But that’s just the innocent start, because then we get Crafty, the Wile E. Coyote lookalike, who challenges this world, challenges GOD.

Animal Man #5 by Grant Morrison and Chas Truog

A comic book character (only created for this issue) challenges its creator to stop using him for violence. This god is a typical god, being merciless and immediately punishes Crafty.

Animal Man #5 by Grant Morrison and Chas Truog

Now Crafty has been put onto Earth, or, well superhero DC comic book earth, where violence suddenly matters and, like it’d happen in any good cartoon, is hit by a truck.

Animal Man #5 by Grant Morrison and Chas Truog

Suddenly violence has consequences and of course the interesting thing here is that in “normal” comic books, violence also often doesn’t have consequences. So, Crafty’s fate is not only unusual for the cartoony world he comes from, but also for the superhero world he is now in. And yet, he persists to try to change things, to “overthrow the tyrant GOD. And build a better world.”

Animal Man #5 by Grant Morrison and Chas Truog

But Animal Man doesn’t understand any of this (yet), so Crafty is left to a fate that gives him no hope and in which his god can just turn his white tears into blood by the touch of his brush, leaving a crucified cartoon coyote Christ figure that is simply heartbreaking. Among the many things this issue achieves, making us question reality and comics and violence and religion, the most astonishing achievement to me is that he turns an adaptation of a cartoon character and makes him more real and emotional than almost any superhero character.

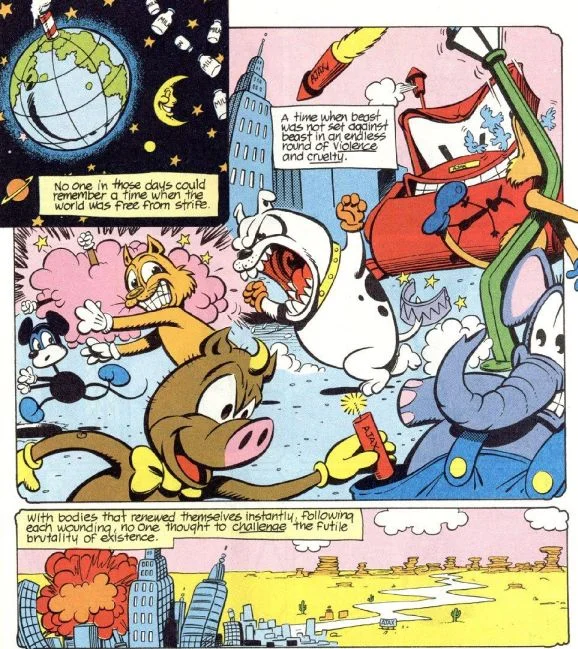

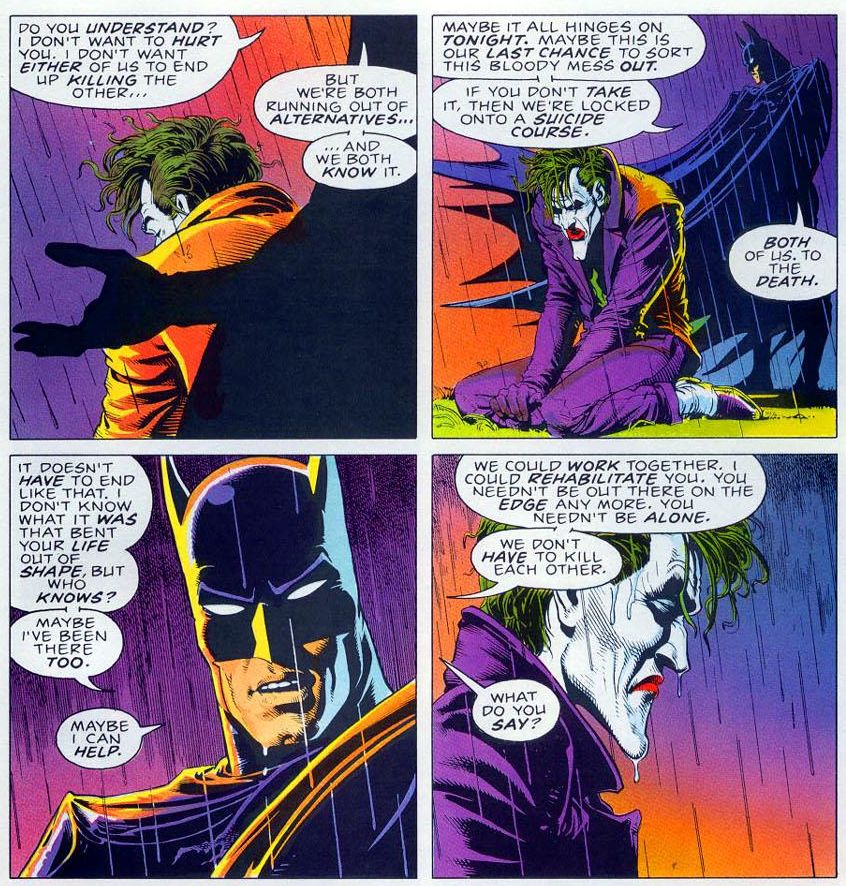

Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s The Killing Joke is seen as an important story in the history of Batman, mainly because of the consequences for Barbara Gordon, but undeniably also because of how it looks at the Joker and Batman.

Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

The comic is mostly famous for this page and there is criticism that disabling Barbara Gordon is just a plot device and therefore misogynist. Moore has some trouble with the comic himself and I personally do find this and the later scenes of torture problematic, too. It’s just unpleasant to see her so helpless and victimized.

Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

But what the story actually is about the idea of madness not as a psychological disorder, but as an escape hatch from what we encounter every day in our society. The Joker argues that it makes things easier because you don’t have to think about them anymore.

Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

He goes even further by claiming that madness is the only possible response to “today’s harsh and irrational world.” It’s a very intriguing thought that might be an answer for many people we claim are “crazy.”

Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

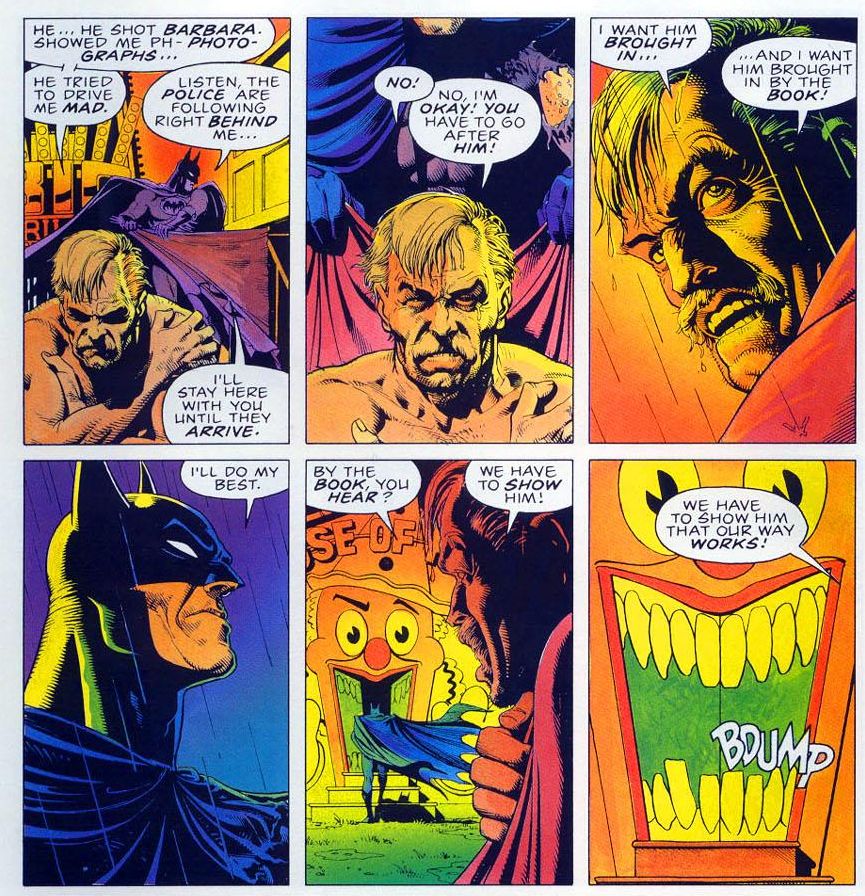

Now Batman comes in and tortured Commissioner Gordon urges Batman to bring the Joker in “by the book!” because “We have to show him our way works.” The world the Joker is talking about is pretty much proof that it doesn’t work, that we are striving for an ideal of laws and rules, that is impossible to achieve, no matter how hard we try. I wonder if Moore agrees with Gordon or not.

Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

Well, here Batman makes an offer to the Joker, which also isn’t straight “by the book.” He in a way admits that they're are both crazy, since they only fight to the death, which is never a reasonable strategy. This whole scene is very unlike Batman and it’s why I like it.

Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

The response by the Joker is a joke and the book ends with both of them laughing together, making it clear once again that the divide between hero and villain is not as big as it normally seems. It’s a notion both Scott Snyder and Christopher Nolan have picked upon since then, but I’d say they didn’t do it as well as Moore here in that final scene.

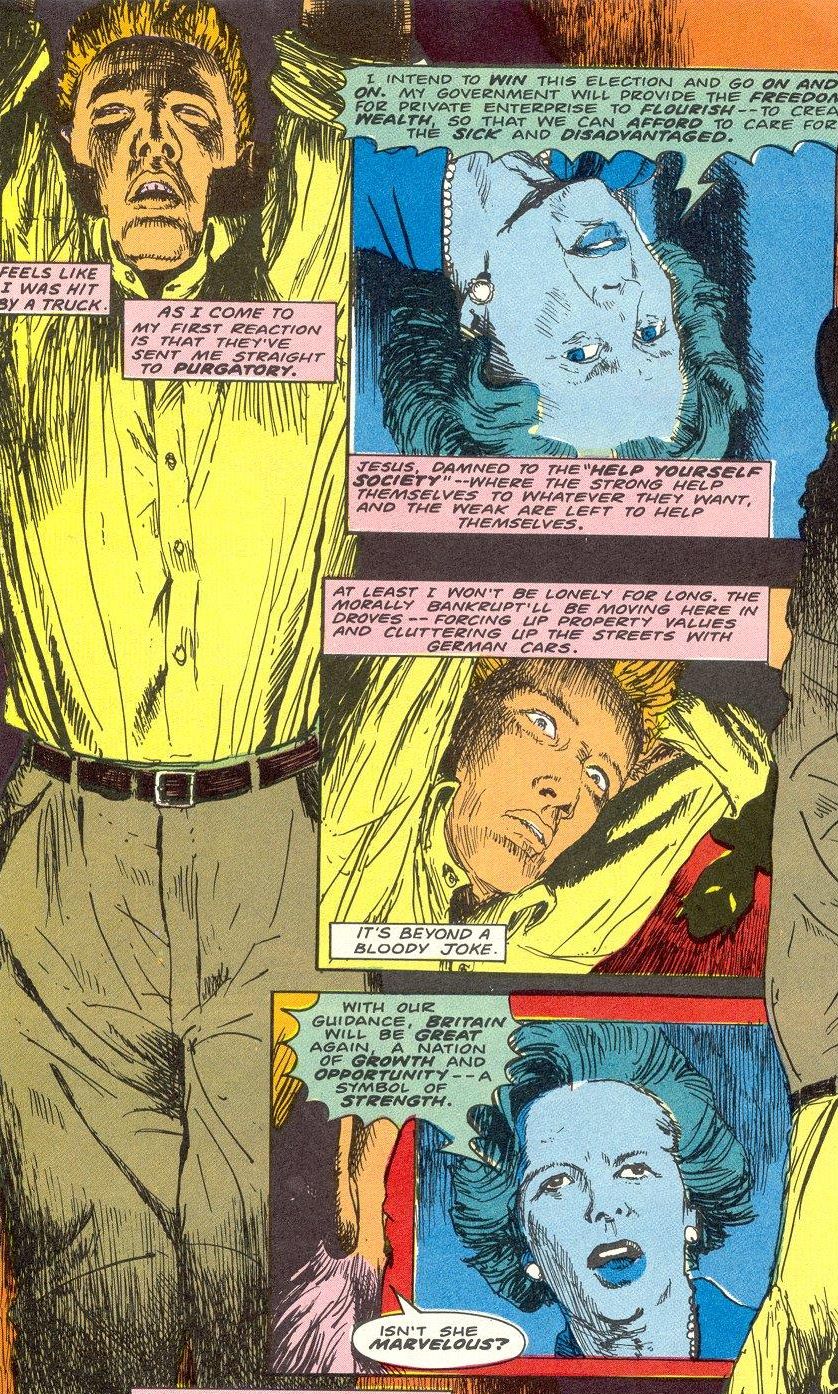

Hellblazer was, just as Animal Man, about to become one of the first “Adult” titles under DC’s Vertigo imprint. And its first year is simply amazing and would continue to be amazing.

Hellblazer #3 by Jamie Delano and John Ridgway

What I love about Jamie Delano’s run, is how he incorporates the zeitgeist of the 80s in Britain, the desolate atmosphere under Thatcher, an end of the world-feeling that is unparalleled and had been going on since the 70s. The credits page of issue 3 features this election poster with the added commentary that makes it clear that the government is just out to exploit people and isn’t really interested in them. How better to illustrate this with a corpse on the pavement?

Hellblazer #3 by Jamie Delano and John Ridgway

John Constantine then walks onto the scene, seeing a society full of poverty, decay and “abandoned people”, abandoned of course by the government and just sarcastically mentions the “return to Victorian Values.”

Hellblazer #3 by Jamie Delano and John Ridgway

Later we see him hanging upside down with visions of Thatcher, dismantling her political propaganda. I just love the ballsiness of this. Can you imagine such a direct political commentary in a comic today?

Hellblazer #4 by Jamie Delano and John Ridgway

Here we have a kid contemplating how unfair adults are treating her, another kind of commentary on how our culture deals with children (who only because of that treatment fall prey to demons).

Hellblazer #4 by Jamie Delano and John Ridgway

More zeitgeist as we get some Nazi youths being sprayed by Constantine. Are they using that in his new TV show?

Hellblazer #5 by Jamie Delano and John Ridgway

And because even in 1988, this wasn’t really done with, we get some images from the haunting nightmare of Vietnam, calling it “everybody’s war” and then dismissing the movies of that decade as a misrepresentation of reality.

Hellblazer #8 by Jamie Delano and John Ridgway

We get more apocalyptic visions by a priest damning progress and riding on a wave of panic and world weariness.

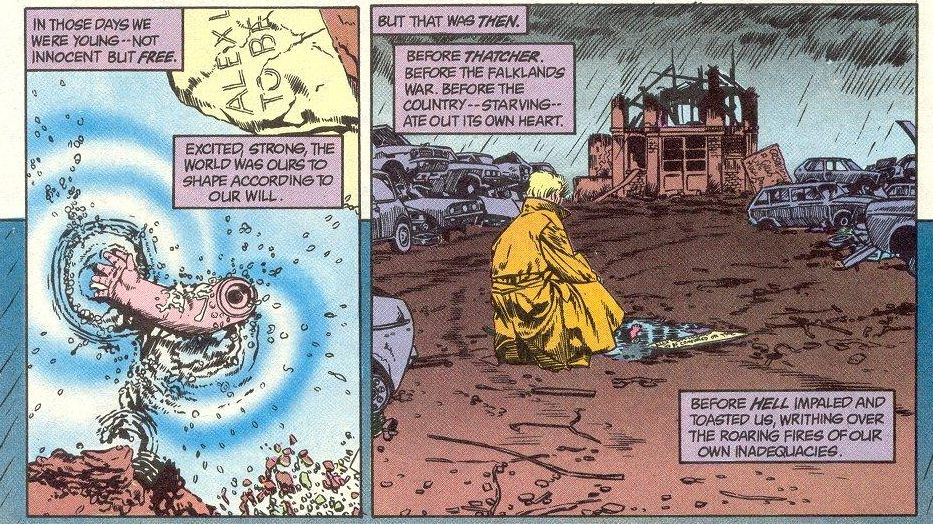

Hellblazer #11 by Jamie Delano and Richard Piers Rayner

In issue 11, Constantine again sees the present with Thatcher and the Falkland War as “hell”, again reminding us why people celebrated when she died.

Hellblazer #13 by Jamie Delano and Richard Piers Rayner

On the Beach deals with the fear of a nuclear plant explosion, relatively fresh off of Chernobyl.

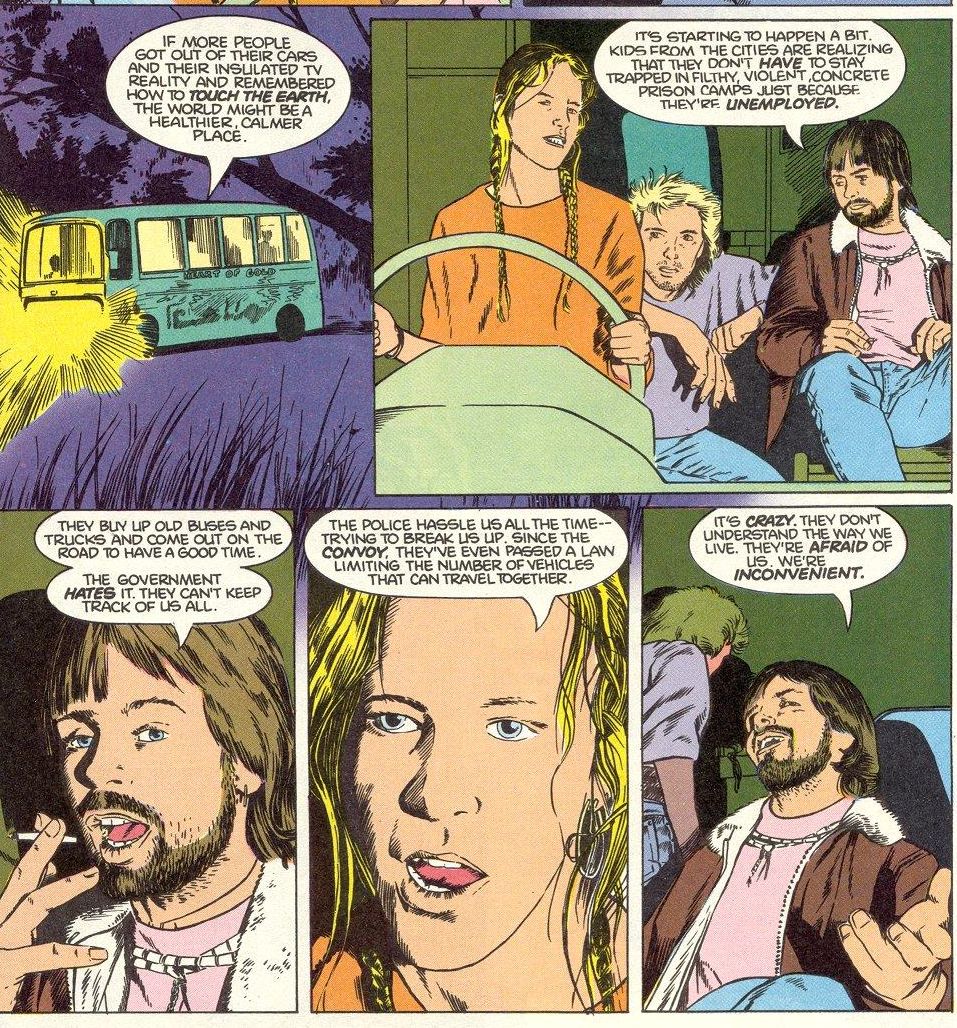

Hellblazer #14 by Jamie Delano and Richard Piers Rayner

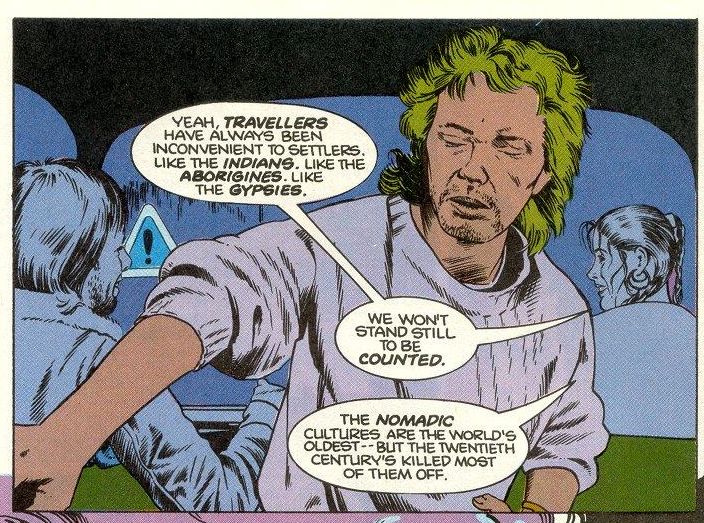

And the beginning of a storyline called The Fear Machine featured Constantine exploring some alternative ways of life. Delano somehow manages not to make them sound like stupid hippies too much and actually allows them to have a point. And what better way of underlining that by having one of the most cynical characters in comics actually consider it?

Hellblazer #14 by Jamie Delano and Richard Piers Rayner

The talk about “nomadic cultures” clearly refers to non-civilized, tribal cultures, which is so rare to read anywhere in a appreciative way, I can only applaud it (though it is something later Hellblazer writers also at least played with, but no one as clearly as Delano).

That was a long post, but I really wanted to share my appreciation for those comics, especially since they are so much of its time, which is the point of this whole week. Now I actually long for the days where such comics were possible, especially at DC. But, yes, there are still good comics around nowadays and enough old stuff for me to discover, but some of these issues here are just phenomenal.