Comics Are for Everyone: Civil War #1-7 (2006)

/Civil War #1-7 (2006-2007)

Written by Mark Millar

Pencilled by: Steve McNiven

Inked by Steve McNiven, Dexter Vines, Mark Morales, John Dell, Tim Townsend

Colors by Morry Hollowell

Letters by Chris Eliopoulos

(spoilers ahead)

The original Civil War comic is undeniably intriguing but also flawed in its execution.

Civil War by Mark Millar and Steve McNiven has become a fixture in relatively recent comic book history. It was hugely successful, inspiring the latest acclaimed entry in the Marvel movie franchise, but also incredibly divisive. This is nothing new to Mark Millar who at some point in his career decided to just write stories that would anger some part of his audience while another part would celebrate it. Civil War is less extreme than some of his other work (Wanted, Kick-Ass, Chosen) but still turned everything readers knew about the Marvel Universe on its head, not just within the limited series he wrote, but also for arguably three to four years afterwards as the consequences of this storyline effected other stories. As proof for its lasting legacy you can count the movie but also the fact that Marvel publishes Civil War II in 2016, not written by Millar but by comic book event expert Brian Michael Bendis.

But let’s focus on the actual comic book for now, the limited run of Civil War, published in the summer and fall of 2007. Again, it was really successful commercially but some critics outright hated it. The inciting incident concerns the New Warriors, a group of C-level superheroes who catch villains for a reality TV show.

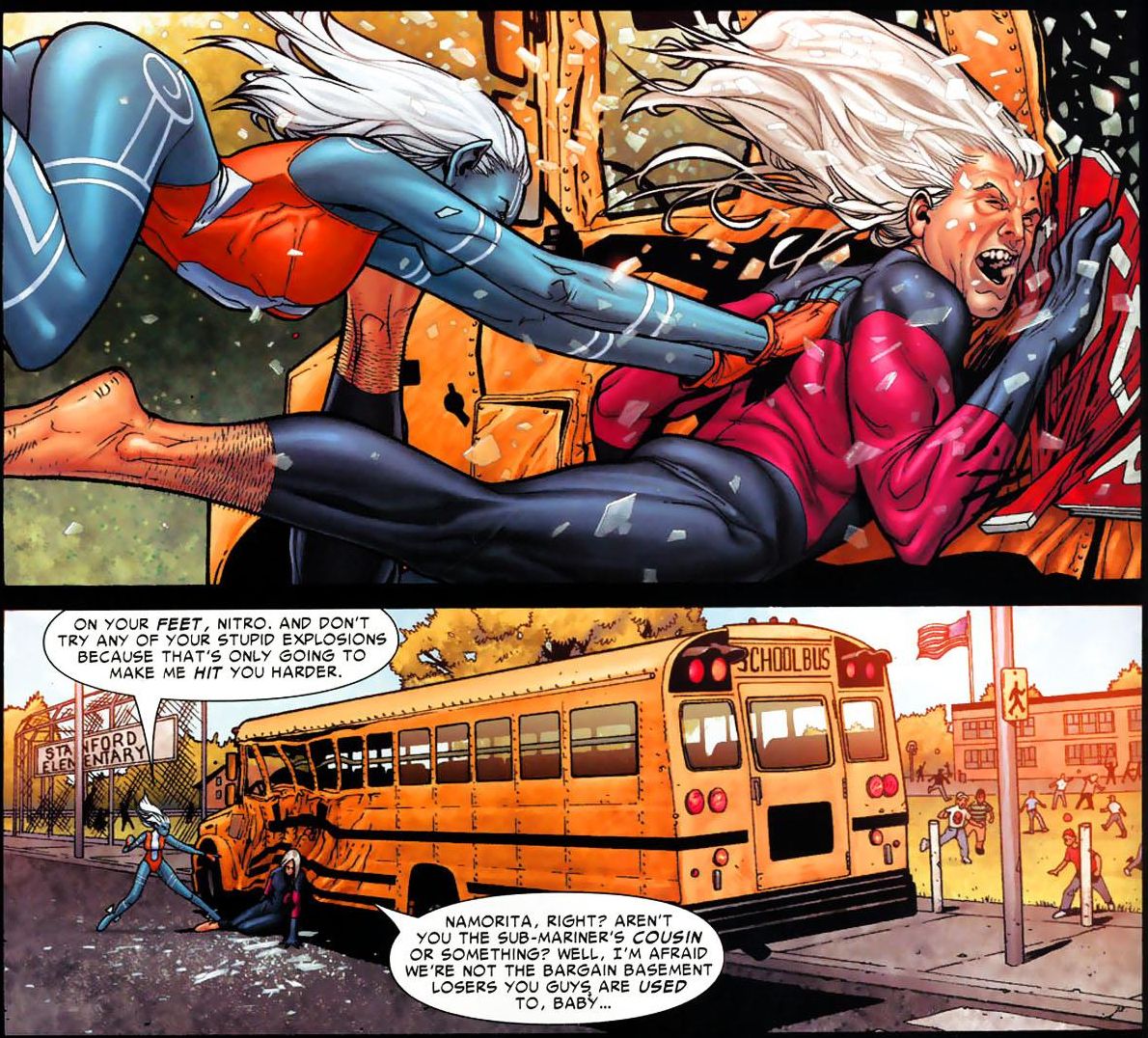

This dialogue is very typical for Millar, focusing on purposely controversial, annoying statements that turn characters into assholes. It also showcases one of the main problems of this comic, that it reduces its conflict to simplistic extremes without any grey area.

Here we see the actual basis for the conflict, namely the collateral damage that happens whenever superheroes and supervillains fight. It is really an intriguing issue to dive into and that image of the school bus and the children close to the carnage does a nice job of conveying that.

But that is not enough for Millar, so instead we get a full-blown explosion, incinerated children and all. The idea of course is that this incident has to be strong enough to stay in the readers’ mind for the rest of the series to remind them why everyone is fighting. The way it is presented and used, though, is another sign for Millar’s style, going for the event and the bombast instead of nuances.

The aftermath is depicted in the same way, with one of the mothers who lost a child accuses Tony Stark for the explosion because his “dirty money” funded the New Warriors. While this conversation (or rather monologue) lays the groundwork of one side of the conflict (superheroes should be registered or else they are just vigilantes), every argument falls victim to the creator’s extremist style. The mother’s last line serves as one of those arguments you can’t argue with but is never seen as a grieving mother’s desperation. Drawing her with the eyeliner running down her cheeks just underlines the extremes. The argument of the relationship between superheroes and the law is there, but it is all about blame and guilt instead (and the real questions of collateral damage caused by superheroes or where the line between hero and villain is are neglected).

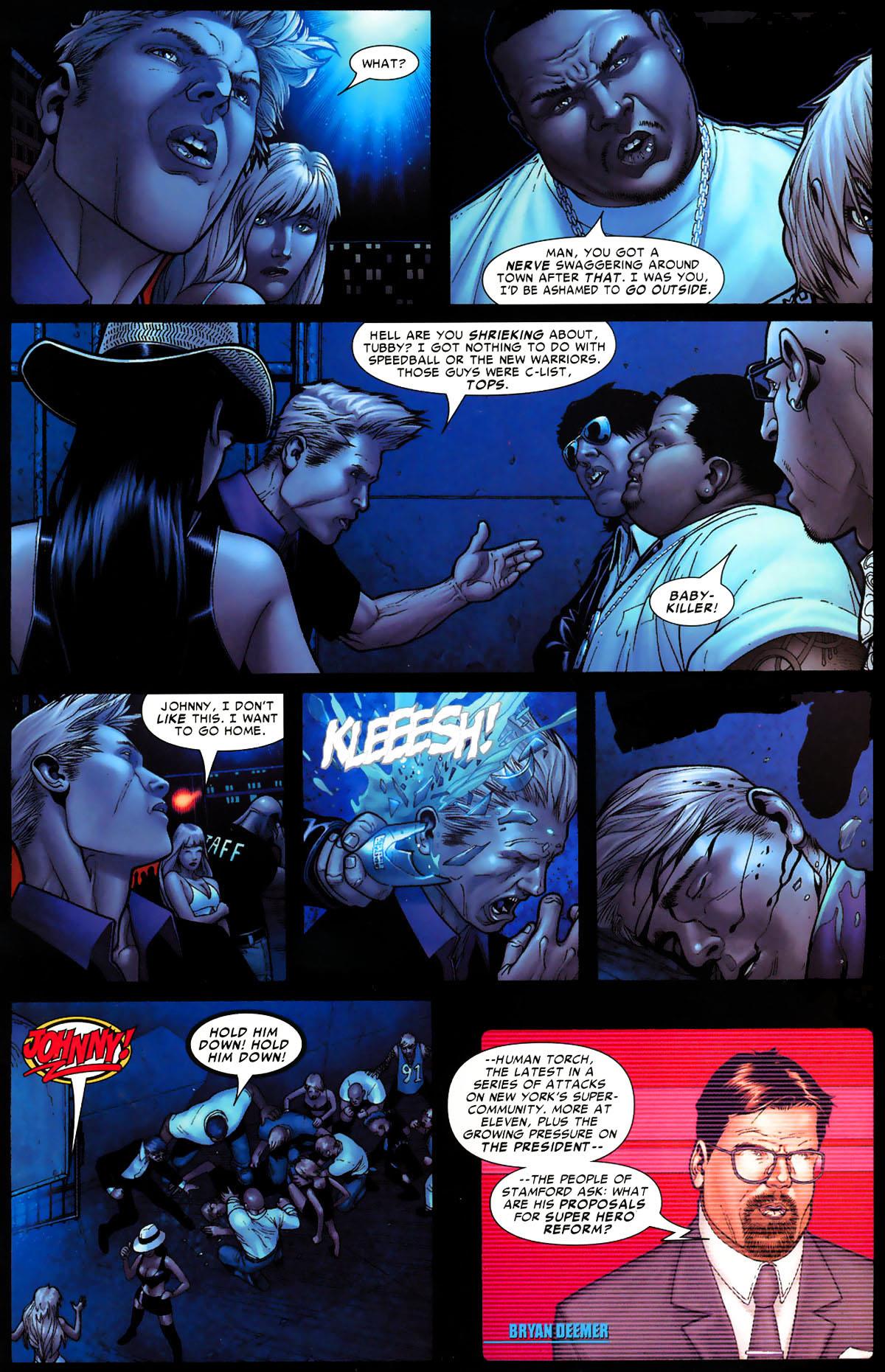

To heighten the conflict (we are still in the first issue), Johnny Storm is attacked by civilians simply because he is a superhero. Studying this page (and I’m repeating myself here) serves as the perfect distillation of Mark Millar in general. Some raw emotions ready to boil over, phrases that evoke historical and political references (“Babykiller!”) without actually having anything to do with it, followed by violence and media outrage. It is a manipulative formula that, again, avoids discussing issues by instead bashing them against each other.

Or there is a throwaway line like this, as the side who is against the new registration laws call themselves Resistance, which again seems to overstate the relevance of the whole conflict, especially if that conflict is never really explored in that comic. There is no real justification for using that term here (besides Millar’s love of loaded words).

And here, for yet another heavy-handed dialogue full of overblown symbolism, Daredevil accuses Tony Stark for being Judas. This serves as a good example that the underlying conflict is clearly one-sided in its depiction. Tony Stark comes off as the bad guy so clearly, which might not be bad by itself (as there might be an inclination to favor personal freedom over government control), but it would be more suspenseful if you could really see both sides.*

One argument, that is never really investigated, is a lower crime rate because of the registered superheroes (can Millar resist throwing Eisenhower into the mix?). The last sentence about falling buildings reminds you that this comic was seen in many ways as a comment on many policies that had been installed after 9/11 for the sake of security. Those references are pretty much lost on us today (and are completely gone in the movie version) but reading the comic now shows that it doesn’t really work as a post-9/11 analogy. It channels the anger and anxiety of that time well but that is about it.

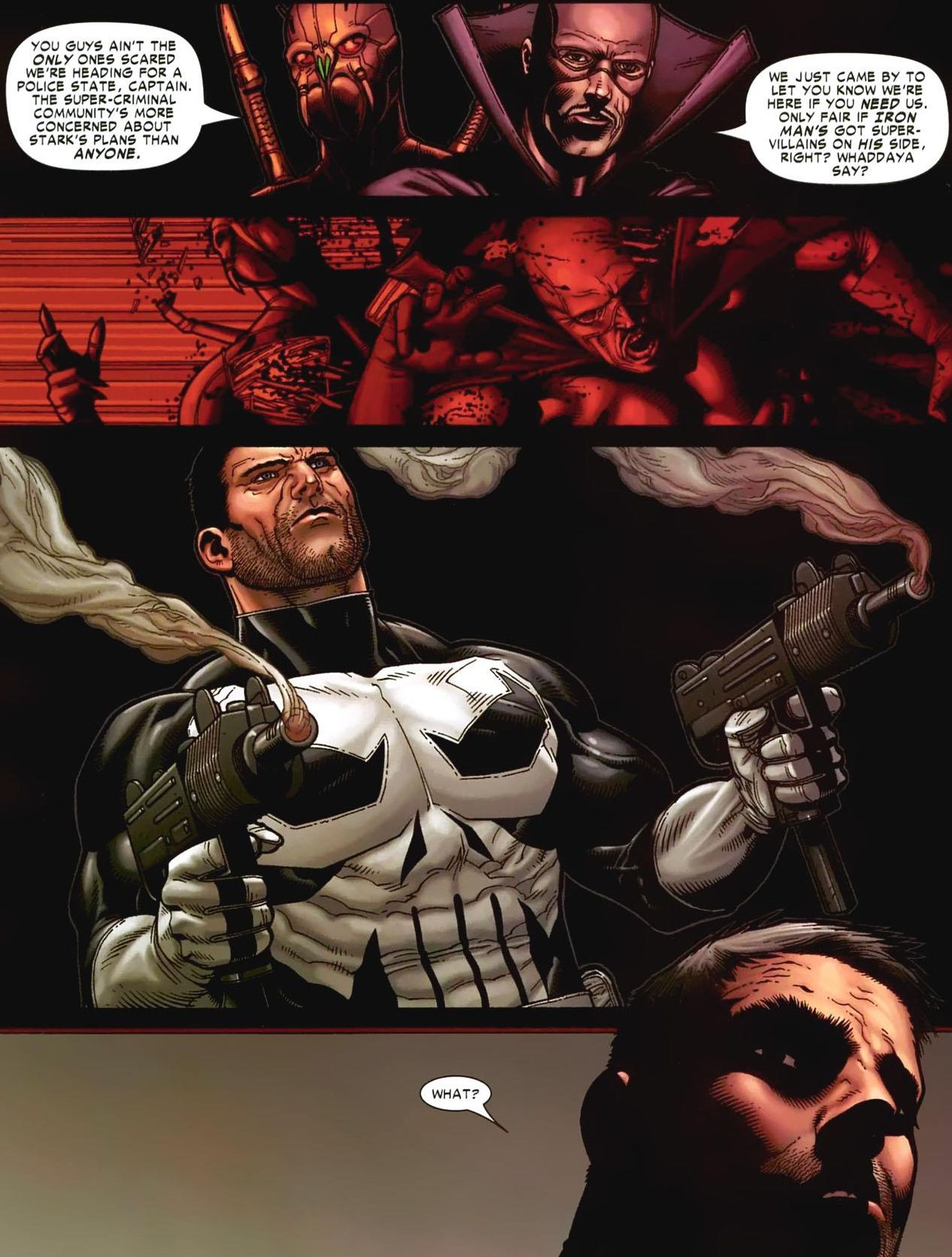

One of the more positive highlights in the comic is the inclusion of the Punisher by Captain America to the so-called resistance. The other members are really skeptical but Captain America insists on giving him a chance. But the first moment he gets an opportunity, Frank Castle just kills some villains who offer to join their cause. Characterizing the Punisher as a total lunatic who doesn’t even understand that killing someone might be bad is one of the more entertaining choices in this comic. It is funny but also shows the lack of judgment that has invaded the conflict at this point.

Finally, the worst part of the whole series is also one of its last pages. After endless fights, destruction and even the death of a superhero, Captain America suddenly has an epiphany and simply ends the fight. It comes out of nowhere and looking at those panels almost brings down the whole book. That Cap’s reasoning for ending the fight is that they are only fighting without winning the argument is so far-fetched and out of the blue, such a contradiction to everything that has happened before that it is hard to believe even for a second. Instead of using any chance for actually following the conflict through, the story simply ends on a whim. It is also pure hypocrisy because Cap has a change of heart because he realizes they only care about the fighting anymore in a comic that only cares about the fighting instead of the issues.

When I read Civil War for the first time, I really liked it but I had just started to get into comics and I was easily impressed. I liked the conflict (and the way it worked in Front Line), the art and the slickness of the dialogue, but reading it again in advance of the movie, shows me all the flaws very clearly, in a painful way. The writing is the main problem here and maybe I had to read more by Mark Millar to see his shortcomings. Or maybe the comic just doesn’t hold up very well. Considering all of this, it is really a relief that the filmmakers decided to discard most of the comic for the movie version and just used its premise to make a much more compelling story. Civil War is not necessarily a bad comic and it is more appealing than many other crossover events but it wastes a lot of potential for provocation, bombast and one-liners.

*For a much more interesting depiction of those and many of the other themes that could have been explored through this conflict, read Civil War: Front Line by Paul Jenkins and various artists, that tackles many civil rights issues, wars and other historical events through the lens of this conflict while also really contemplating each side of the argument. I might analyze this too in a future article.